By: Tamer Amr

The state is moving towards upgrading specialized industrial zones into fully-fledged cities, coming in line with President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi’s directives. The main advantage of having specialized industrial cities spreading across the country is that they aid the sector’s players to achieve economies of scale and create a more effective supply chain to meet local and foreign market needs. Accordingly, businesses will find it easier to upgrade their manufacturing technologies and ensure having a suitable infrastructure.

During a press event last June, Presidential Spokesman Bassam Rady said:

“[The industrial cities] would be built around labor-intensive industries such as textiles, automotive, carpets, and automobile. The president highlighted Robeky City and Damietta Furniture City as two prime examples of industrial cities and directed the government to build more of them.”

CEO of Saudi Egyptian Construction Company (SECON) Darwish Hassanien highlighted that there are other industrial cities under construction such as New Assiut, which would be dedicated to micro- and small-industrial enterprises, while CEO of the General Authority for Investment and Free Zones (GAFI) Mohsen Adel further added that New Minya as a city anchored by construction materials investments, given its proximity to the mineral-rich Eastern Desert mines.

New Industrial Cities Come With Real Estate Development

The government continues to build specialized industrial and investment hubs nationwide. However, the challenge of making them successful will be to ensure that real estate and industrial complexes are built simultaneously. Private developers see that linking industry and investment with real estate development is increasingly beneficial for them in terms of a number of investments and residents, who are in need for residential and commercial properties to serve workers in these locations.

Abdel Nasser Taha, president of the International Real Estate (FIABCI-Egypt), notes:

“Real estate in Egypt is going through a proverbial fork in the road. For local developers to continue to grow, they need to align their construction progress with industrial development, especially among sectors considered a priority by the state.”

SECON’s Hassanien tells Invest-Gate:

“It is no coincidence that Sadat City is an industrial city and is one of the most populated compared to similar cities in Egypt. People look for jobs over there so they can relocate there once they find a suitable home,”

Right now, Hussein Sabbour, chairman of Sabbour Group, believes that Egypt’s industrial zones are lagging behind in terms of real estate development. He highlights:

“Government policies are encouraging domestic industry. But to achieve sustainable development, real estate needs to meet housing needs arising from these projects. [investing around an industrial zone] is a big opportunity for local developers to find sustainable growth.”

According to Adel Lotfy, head of the Egyptian Real Estate Developers Council:

“Technology will likely be the key to establishing the link between the industry and real estate developers, A published digital map of all this information, coupled with favorable investment laws specific to industrial city investments, will be the building blocks leading to the success of any industrial city.”

Building Industrial Communities

Robeky City is Egypt’s first specialized industrial city, located four kilometers away from Badr City along the Suez-Cairo highway.

Robeky City is Egypt’s first specialized industrial city, located four kilometers away from Badr City along the Suez-Cairo highway.

Hamdy Harby, a former head of the Leather Industries Chamber at the Federation of Egyptian Industries and owner of three workshops in Robeky, says:

“Robeky City’s maximum capacity is 50,000 employees. It is supposed to start a socioeconomic revolution in the area, similar to what Magra El Oyoun did in its heyday.”

As of 2018, there are over 1,000 residential units built just 750 meters from the industrial area. “This is not enough given how active Robeky is right now,” Harby notes. This housing development is designed to have facilities such as a hospital, school, police station, and banks. “However, no one (neither individuals nor businesses) moved there despite its launch back in March 2018,” he says.

Speaking of the services of the new city, Mohamed Zaki, a 37-year-old third-generation leather tanning workshop owner living in Magra El Oyoun, comments:

“The facilities are just enough for workers to hangout, eat, drink, and smoke on their breaks. A major problem facing Robeky is lack of infrastructure, given that there is a single 10-meter-wide road connecting the workshops with nearby Badr City. There is no government transportation services along this route. Instead it is handled by unregistered privately-owned micro busses and tuk-tuks (auto rickshaws).”

“Another problem facing relocation to Robeky is that it only offers facilities for burning workshops, waste, rather than burying or chemically treating it, which is environmentally safer. This makes living there really difficult with all that pollution, which will rapidly increase as more workshops move into the city.”

Benban Village, which lies 61 kilometers away from Aswan, was commissioned in 2014 to become one of the world’s largest solar parks with local and foreign investments already pouring in.

Benban Village, which lies 61 kilometers away from Aswan, was commissioned in 2014 to become one of the world’s largest solar parks with local and foreign investments already pouring in.

Pollution is a matter that Benban Solar Park, at Benban Village, does not have to worry about. It is currently an investment hotspot for clean energy and solar power stations thanks to the legislation passed in 2016 that allows private power stations to feed the national grid.

Aswan Governor Magdy Hegazy told reporters last December, after a meeting with delegates from the World Bank:

“We are aiming to turn Benban into a stand-alone city. I have to admit that residential development around the solar park, until now, had taken a backseat to station investment.”

To rectify this, Hegazy has been in negotiations with private investors to build residential and commercial units for up to 5,000 employees, who will be working in the power stations when the solar park reaches full capacity.

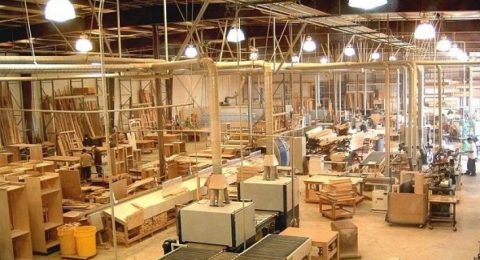

Meanwhile, Damietta Furniture City is still in the planning phase. It aims to attract all of Damietta furniture workshops and seeks to give furniture-making in Egypt a technological uplift and to create a significantly more efficient supply chain.

Meanwhile, Damietta Furniture City is still in the planning phase. It aims to attract all of Damietta furniture workshops and seeks to give furniture-making in Egypt a technological uplift and to create a significantly more efficient supply chain.

Speaking at a press conference last October, Damietta Governor Manal Awad noted:

“The new city primarily aims to relocate the governorate’s workshops as well as attract new investors with a maximum capacity of 30,000 permanent jobs. So far, over 1,340 workshops have been built, all are pending allocation to local furniture makers. Damietta Furniture City is planned to include commercial spaces, a conference center, hotel, and other facilities.”

Founder and Chairman of El Gabry Group for Real Estate Development Mohamed El Gabry remarks:

“There are no dedicated plots for residential developments around the furniture city. The launching of New Damietta City has opened up a lucrative opportunity for El Gabry to be the first to provide homes and services to the workers in Damietta Furniture City, by constructing a gated complex a few kilometers away.”

“I have been talking to some other developers and they too seem interested in capitalizing on Damietta Furniture City. It is guaranteed that this will still be a few years away until the new city has enough foot traffic to increase the need to relocate closer to the workplace.”

A Question of Sustainability:

According to Abdel Raham El Gabbas, member of the Leather Industries Chambers:

“Residential developments linked to industrial areas must be expedited. We are hearing more complaints from owners and workers about the commute and lack of services in Robeky, for example.”

For Hegazy, while the government is building social housing units in major existing cities near up-and-coming industrial cities, private developers need to start constructing projects within these specialized industrial hubs to turn them into cities – something which is yet to happen in Benban. He says:

“The lack of such developments greatly threatens the prospects of Benban reaching full capacity, given that the original village was never designed to have such large scale investments and that huge influx of people.”

Meanwhile, private developers must adapt to critical differences when investing in an industrial city, including the need to work more closely with the government and local society to build homes that would meet their demands and capabilities, as well as, match the nature of the industry that the city is built around.

To learn more about this topic, read pages no. 28-31 in our February issue.